Sense your body

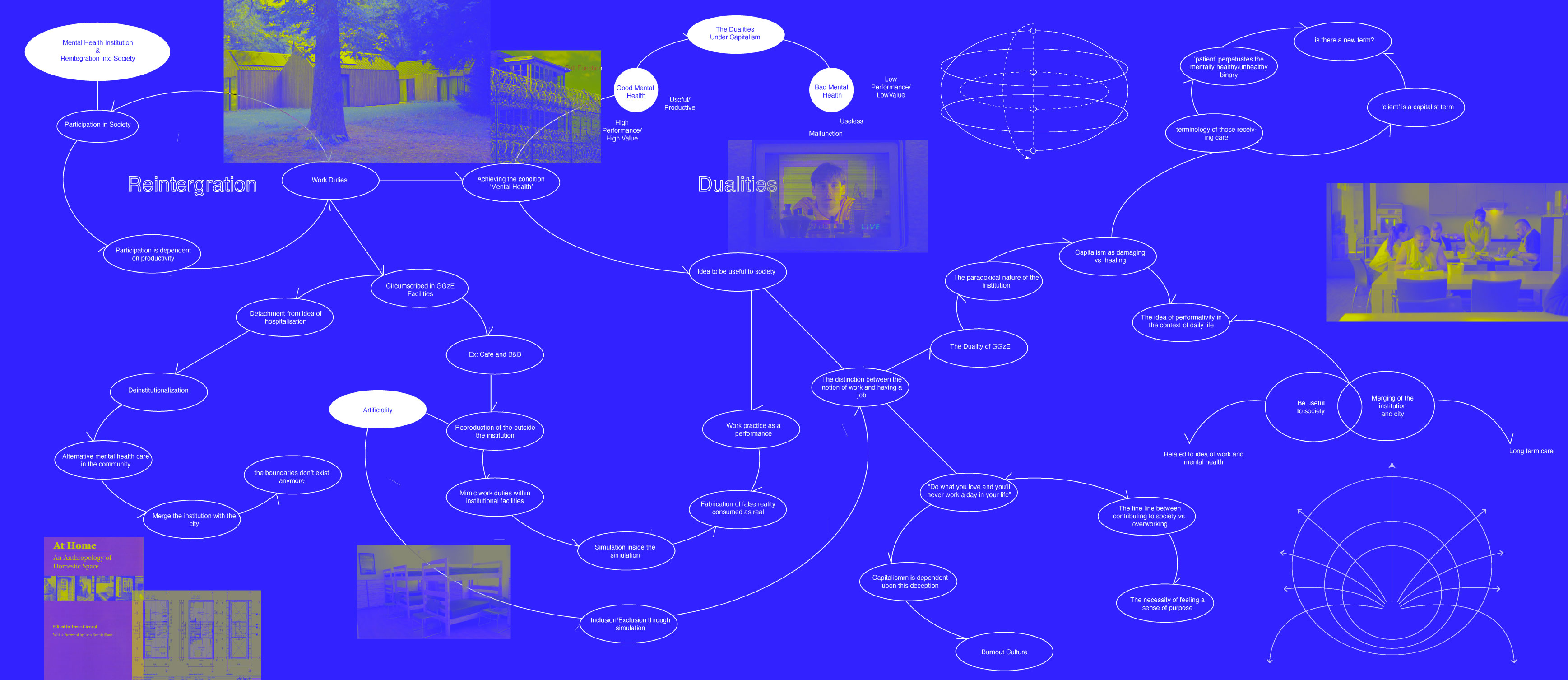

A NON-CAPITALIST SELF-CAREThis project started from a critical awareness that the care model of the Dutch mental health institution GGzE is based on a capitalist framework. One of GGzE’s primary goals is to reintegrate patients as productive members of society. We recognized that capitalism can be inherently harmful to human beings, yet we also acknowledged that it is the ideology we currently inhabit, and asked: how could this capitalist framework become a more grounded, human experience?

GGzE operates a rehabilitation model aimed at the social reintegration of clients. The ultimate goal of this model is to enable clients to live independently, without requiring professional support. We observed that clients’ return to society is facilitated through simulations of daily life, particularly work and labor duties. Even the use of the term “client,” replacing “patient,” attempts to transcend the healthy/unhealthy binary, yet it is itself a capitalist term, the same used for a paying customer in business contexts.

Within GGzE, various service spaces—cafés, bicycle repair shops, and accommodations—depend on the labor of clients. We discovered that this care model embeds a level of performativity: clients must perform everyday life to prepare for reintegration into society. Being recognized as a socially valuable individual requires productivity, which becomes a standard for mental health. This binary reduces human complexity, simplifying people into functioning units—a clearly harmful oversimplification.

Furthermore, a physical and symbolic boundary exists between GGzE and the city. Deinstitutionalization seeks to dissolve this separation, integrating care into the urban environment.

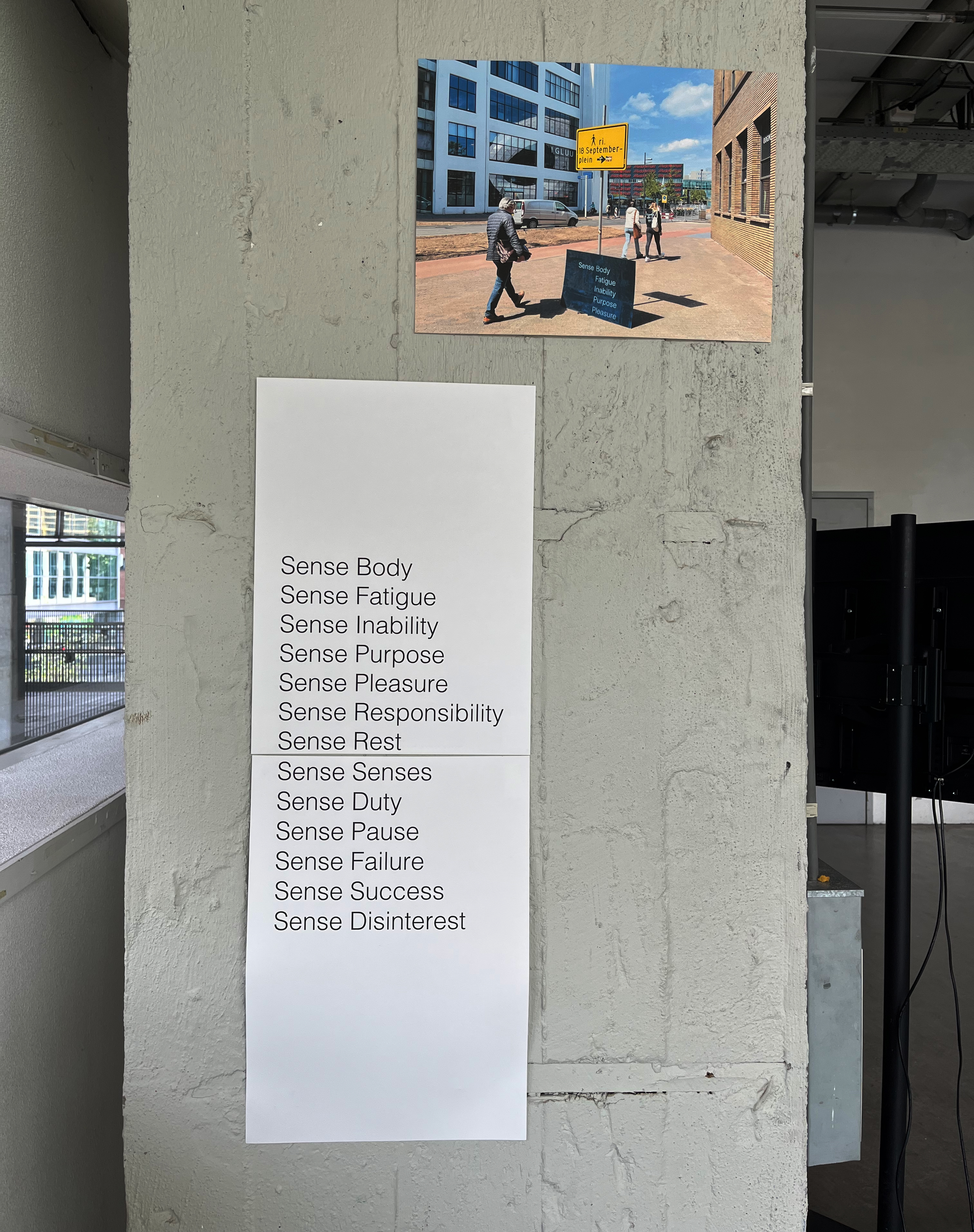

Within this context, we reappropriate the LED sign as a deliberately uncomfortable device. In capitalist cities, LED signs are a familiar form of command: they tell people what to buy, how to act, and what kind of life to pursue. We adopt this form to display messages of care detached from productivity, such as “rest,” “sense the tension in your body,” or “doing nothing is allowed.” These phrases may appear comforting, yet they also risk functioning as another form of obligation or subtle pressure.

The signs are distributed throughout the city, rather than confined to GGzE buildings. This placement makes visible that mental health is not isolated within an institution but continuously produced within the rhythms and pressures of urban life. At the same time, it gestures toward the possibility of deinstitutionalization, yet this expansion is not a safe liberation—it may introduce new forms of exposure and surveillance.

This project does not provide care, but problematizes the way care itself operates. By acknowledging that these LED signs could easily be absorbed as normative self-management tools, the project examines how critical interventions risk reproducing the structures they seek to critique. It asks: where does ethical intervention begin, and where does it become complicit?

Designers Giulia Braglia, Holly Zambonini and Yujin Joung

Collaboration GGZE Eindhoven